I recently came across a fascinating archive of colour photos, all taken in pre-Soviet Russia circa 1910. The photographer, Sergei Prokudin-Gorski, developed his own colour process using filters and three separate plates - it has taken the advent of digital technology to produce a clear colour composite from the process and now the photos, all in the archive of the Library of Congress, sparkle as if they were taken yesterday. I've been on a Russian reading jag recently - I especially enjoyed Orlando Figes's A People's Tragedy - and these photos depict how strange and often backward, to Western eyes, Russian culture was.

Cotton was a major contributor to the Russian economy. Throughout this period Russian agriculture was primitive, as in many areas a system of collective ownership, or Obschchina, tended to remove incentive to develop arable land. The cotton and dyeing industry is poorly-documented, but Prokudin-Gorski's photos provide a tantalising glimpse.

This is the interior of a textile mill - using the local cotton - probably in Tashkent. Any guesses as to the machines and particular parts of the process gratefully received!

A cotton field, in the Sukhumi Botanical Garden.

I love this photo of a fabric merchant at the Samarkand market, because the colours are all true, not hand-tinted. Note the framed page from the Koran at the top of the stall. Like the others, this photo was taken around 1910 and depicted a way of life that more or less disappeared within a decade.

Other glimpses of the diversity of culture in the pre-War period

Thursday, 22 March 2012

Friday, 16 March 2012

The many political hues of Indigo

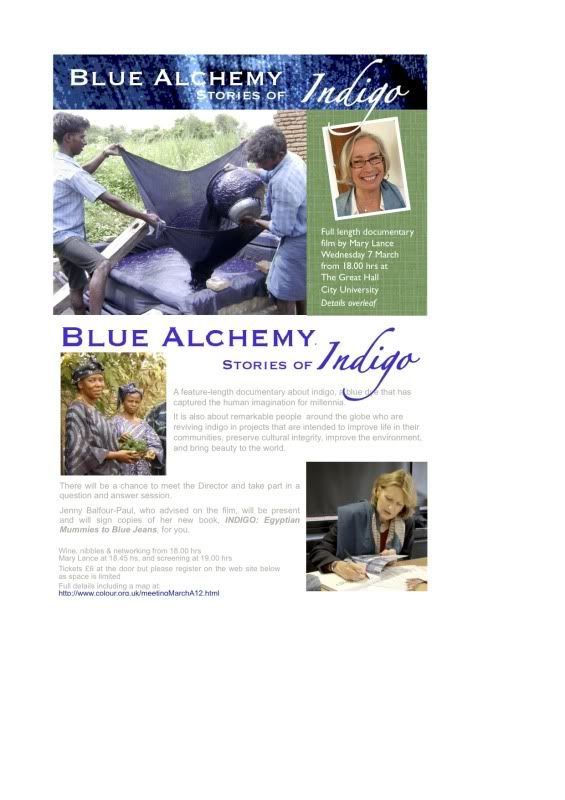

Mary Lance's new film on the history of Indigo, Blue Alchemy, is an intriguing work on many levels, some expected - and some surprising.

It was perhaps inevitable that, with a consultant like Jenny Balfour-Paul, author of the landmark (and recently republished) Indigo, it would be a fascinating examination of the diverse forms and techniques associated with indigo - there are many insights into the history of this fascinating dye, and throughout there's a wonder at its strange alchemy, of how a liquid that's a yellowy-green colour can turn fabrics, especially cotton, blue. The insights into the intricacies of indigo, how its use developed in different continents, and the way its heritage varies across the globe, are manifold. Throughout the film, there's an engaging focus on people, and how indigo permeates their lives, such as the wonderful Hiroyuki Shindo, who maintains the tradition of Sukumo, the composted leaves of Polygonum Tinctorum, using this ancient Japanese technique to create beautiful, serene artworks.

Hiroyuki Shindo - an exponent of the Sukumo, the traditional Japanese technique of making an indigo compost (European woad dyers used a similar technique). Photo by Mary Lance.

The contrasting, more sophisticated technique, perfected in India, using the Indigofera Tinctorum plant. This produced an indigo "cake' that was easily transportable. These methods were copied (perhaps via industrial espionage) in Jamaica and South Carolina. Photo by Mary Lance.

Yet the fact that struck me most forcefully is that indigo is a political subject, which inevitably reflects the power structures of the world around it. This is an issue which surfaces in Jenny's book, where she discusses the dye's early history alongside that of Tyrian Purple - the colour that was the symbol of power and affluence in the Roman Empire; the history of indigo similarly stretches right back, to the second millennium BC, when it was used to colour the pharoahs' clothing. The political resonance of indigo intensified once dyeing techniques reached Europe in the 1500s. The dye was so prized that, from the 1700s onwards, huge tracts of Bengal were used to farm Indigofera Tinctoria; the East India Company and their planters coerced workers to convert their land use from food to the lucrative crop, which was used for dyeing both military uniforms and fashionable items like blue satin. The consequent food shortages, along with the meagre wages, resulted in The Indigo Revolt; a rebellion which many see as the beginnings of non-violent protest, as practised so effectively by Mahatma Gandhi.

As with Sea Island Cotton, and so many of today's fashion items, the popularity of indigo resulted in exploitation and repression; after the Indigo Revolt, indigo culture moved to South Carolina - relying heavily on slave labour. As Lance's film explains, indigo's revival as a craft skill today has required producers in several areas to banish memories of a dark and cruel past.

Yet that dark past didn't recede with the passing of natural indigo. From the 1890s onwards, of course, the advent of synthetic indigo, via a process invented by Adolf von Baeyer, freed many from menial toil. But as Diurmud Jeffries relates in his gripping, but depressing book Hell's Cartell, Baeyer and his company BASF were an integral part of Germany's militaristic revival. By 1915, synthetic indigo had effectively wiped out the natural version, despite the efforts of the British empire. (Even Cone, who started producing denim for Levi's in 1915, are thought to have evaded restrictions on the German product during the First World War, and dyed their denim with synthetic indigo). BASF later became a key member of the IG Farben cartel, using their industrial muscle to bankroll the Nazis, and their huge income from synthetic indigo and other dyes helped fund research for products like synthetic petroleum, to help Hitler achieve his long-fantasied "Autarky" - economic self-sufficiency. When the allies liberated Auschwitz, they found a huge synthetic petroleum plant built by IG Farben, whose directors, according to Jeffries, only avoided the death penalties they deserved thanks to resurgent american anti-Semitism and the advent of the Cold War.

So far, so repressive. But all of human life is there, in the history of indigo. Perhaps the best counter-example to the dark side of the dye comes from the clothing popularised by Giuseppe Garibaldi. For in the Museo Del Risorgimento in Rome there are a pair of blue workpants known as 'Garibaldi's jeans', made from a blue fabric that is possibly a fustian - cotton fill, probably with a indigo linen warp - or a cotton duck. This style of pants became known, of course, as' Genovesi'. Garibaldi, the "Lion of Liberty", was the first rebel with a cause, albeit in Blue Genes, rather than Blue Jeans.

When it comes to totalitarianism vs the individual, indigo has historically backed both sides. Happily, Mary Lance's film gives a warming account of its new role, helping to liberate isolated, sometimes troubled communities, fostering the craft ethic in an increasingly industrialised world.

Tuesday, 6 March 2012

Indigo in London

A quick heads up;

true denim heads will know about Jenny Balfour-Paul, probably the world's foremost expert on the history of indigo. Her definitive book on indigo has recently been republished as Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans.

Blue Alchemy, on which Balfour-Paul was a consultant, is a movie on the history of indigo, and how people around the globe are reviving it in their various communities. Jenny will be signing books after the screening and there will be a Q&A with director Mary Lance.

Screening is 7 March, 2012 at the Great Hall, City University, St Johns EC1V. There is another screening for students at the London College of Fashion on the 12th. I hope to see you there.

Personally, I've learned huge amount from Jenny's book - it's a landmark in the study of the subject, and I suspect the movie will be the same.

I plan to interview Jenny at the beginning of next week; I'm canvassing for questions, so if there's anything you've always wanted to know about Indigo, email me by clicking on the link on my home website.